16.00 Uhr

Konzerthausorchester Berlin, RIAS Kammerchor, Joana Mallwitz

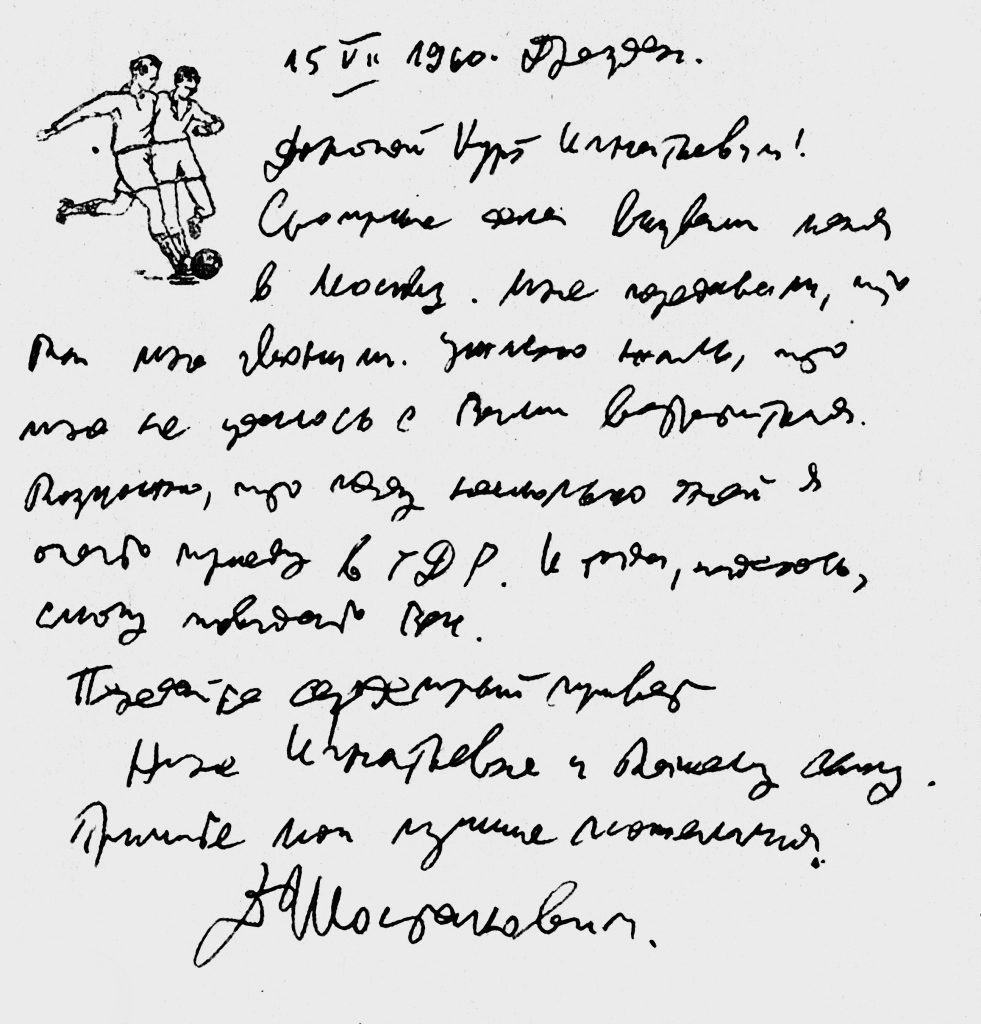

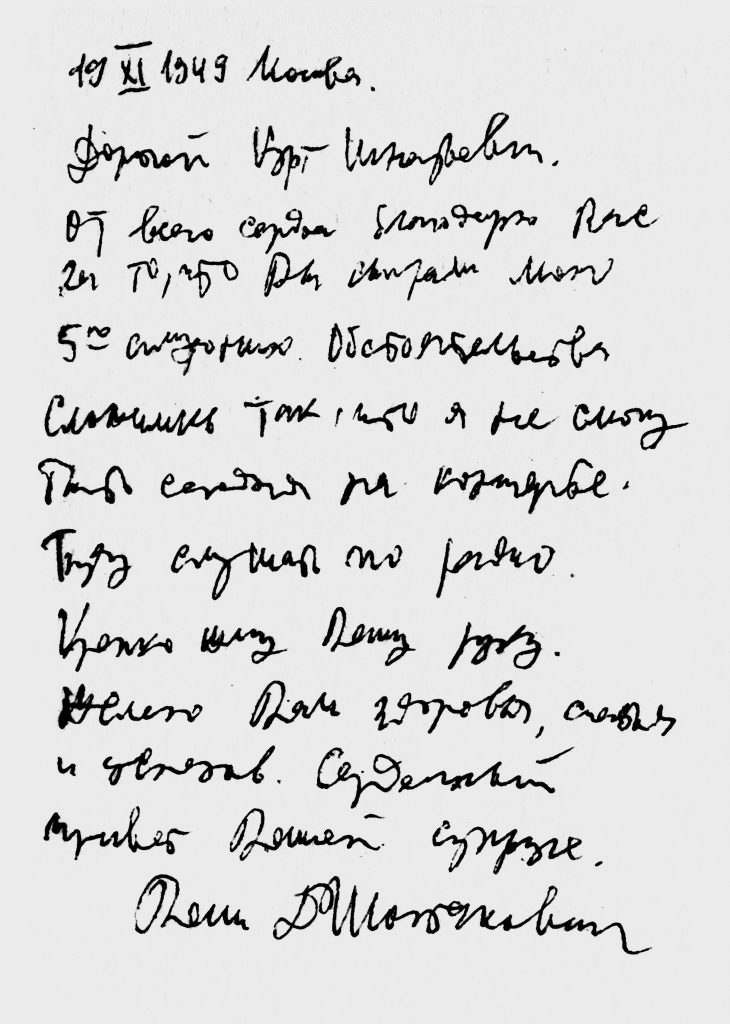

Dmitri Schostakowitsch mit Kurt Sanderling © Archiv Konzerthaus Berlin

Dmitri Schostakowitsch mit Kurt Sanderling © Archiv Konzerthaus Berlin

August 9, 2025 marks the fiftieth anniversary of Dmitri Shostakovich's death. Beetween July 11 and 13, Michael Sanderling will conduct the Konzerthausorchester with his 11th Symphony “The Year 1905”.

His father Kurt Sanderling, chief conductor of the Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester from 1960 to 1977, was a friend of Dmitri Shostakovich and someone the composer trusted. Former members of our predecessor orchestra remember his rehearsals and the legendary recordings of the symphonies from 1976 to 1982.

It was this tradition that our former principal conductor Christoph Eschenbach referred to when he said the orchestra has “Shostakovich in its DNA”.

The double bass player and later professor Barbara Sanderling played in the Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester, the predecessor of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, between 1961 and 1986 – much of the time as a soloist. Married to principal conductor Kurt Sanderling in 1963, she got to know Dmitri Shostakovich’s long-time friend not only in official situations but also in private ones.

“My husband and Dmitri Shostakovich were close, if one can say that Shostakovich was close to anyone at all. He was never prepared to ‘come out’ as a friend. He was far too introverted for that. But of course, the two of them spent long periods of time together. That’s what remained then, this trust. Because he spent so many years in the Soviet Union, my husband had been similarly trained as to what one can and cannot say. Shostakovich also visited us here in our house in Pankow. I would call it a relationship based on equality and respect. He liked my husband and his work. I still remember when we received news of his death in the summer of 1975. That’s when I realised very clearly how serious the relationship was to my husband – what a loss it was for him."

Their two sons Stefan (*1964) and Michael (*1967) are also conductors, and Michael in particular is considered a Shostakovich specialist. The famous guest in his parents’ living room, however, was not someone who dealt well with children: “He was too insecure and nervous for that, frightened by a government that was adept at breaking people. But I believe that just an encounter with someone like Shostakovich can transmit something to children without discussing it with them. It never occurred to us that one day they would perform the music of this ‘uncle’ sitting there. The two boys were definitely influenced by the fact that we recorded the Shostakovich symphonies with the Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester on Eterna Records. They always attended all the concerts. That’s when this familiarity with Shostakovich’s music developed – especially true for Michael, who recorded all 15 symphonies with the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra.”

Andrea Mai, one of the first violins after 1975, vividly remembers recording the Fifth, Tenth and Eighth Symphonies with the Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester: “My first ‘service’ consisted of Brahms’s Second and Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphonies. Kurt Sanderling began with the announcement: ‘Now we’ll all take a little break and I’ll sing you something.’ I was very impressed with the way he took a piece apart – especially the slow movements of the Fifth and the Tenth Symphonies. There were these beautiful melodies – but they weren’t meant to be played beautifully. He brought out a certain colourlessness, a desolation. So quiet, washed-out, anxious and tremulous. He was able to portray exactly what Shostakovich meant. And he took his time. A passage could be played 20 times, if necessary.”

“Later, I also performed Shostakovich with other conductors. But not with the sense of intensity and grasp that Kurt Sanderling always displayed. Sensitivity and compassion, emotional involvement and empathy were his trademarks. Kurt Sanderling was concerned with making a declaration, not homogeneity. This abruptness was part of it. He knew all these pieces first-hand, having witnessed their premieres as second conductor of the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra. Shostakovich did not ever explain his music in this time of fear.

Sanderling paid attention to every little detail during the recordings. The sound engineer he trusted was Heinz Wegner. He often told him: ‘We are in your hands now, Mr Wegner. In the evening, we are in God’s hands.’ The sound engineer, who had a pleasant voice and was very reliable, sometimes took things even more seriously than Kurt Sanderling did. At one point, Sanderling, with his inimitable pouty expression, said: ‘So, Mr Wegner, I think now we’ve got it.’ And finally: ‘That’s good now.’ Then we were done.”

Our former principal flutist Ernst-Burghard Hilse played the Fifteenth Symphony straightaway with the principal conductor in his first programme in 1977: “The first movement begins with two triangle strokes, followed by a longer flute solo. Kurt Sanderling worked on it with me for ten minutes until it sounded exactly as he imagined it. For him, the work was not ‘circus music’ at all, but full of ambiguity. He knew only too well the circumstances of Shostakovich’s life during the Stalin era – that fear of being crushed. Kurt Sanderling possessed the wonderful ability to speak in images and thus illustrate his conceptions of sound. This is how the unique Sanderling colours came about, which can still be heard in the recordings today. I was lucky enough to record the First, Fifth and Fifteenth Symphonies with him.”

Stefan Markowski, associate concertmaster of the second violins until spring 2025 and a member of the orchestra since 1981, also has his own special Shostakovich memories – from a time when Kurt Sanderling had long since ceased to be principal conductor. After all, the Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester was and remained a Shostakovich orchestra: “In 1988, Kurt Sanderling conducted the Fifth Symphony. It was incredibly gripping and emotional. But there was something else – it was one of the last concerts of what was then the BSO before it embarked on a major world tour to England, the USA and Japan. Representatives from the agencies that would supervise the orchestra on this trip were sitting in the concert hall. All the musicians knew that it was a very important concert for that reason. This mixture of extreme tension, the absolute highest level of commitment and a musically magnificent, fulfilling performance by the conductor resulted in a stirring, unforgettable concert that is still vivid in my memory now, decades later.”

Ultimately, Kurt Sanderling himself should have his say. In a conversation the year before his death in 2011, he vividly describes how he internalised the composer’s music as a young man during Stalin’s terror in the late 1930s: “I was part of the first performance of the Fifth Symphony in Moscow [...]. It was indeed the case that after the first movement we looked around sheepishly at the other performers and inwardly asked ourselves whether we were going to be arrested for having heard that. That was the situation back then. And an entire generation accompanying and following Shostakovich could still understand that. Today things are different, of course. Today you hear the oppressiveness of the first movement, and oppressiveness is something that is independent of the respective epoch. So for me, the music has passed the test of time. It is no longer just a description of the era, but has become more instead.”

Photos and letters: From the private archive of the Sanderling family. Cover photo: Kurt Sanderling and Dmitri Shostakovich. Orchestra photo: Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester under Kurt Sanderling, Barbara Sanderling on principal double bass. Letter 1 (Berlin 1960): On appropriate stationery, football fan Shostakovich regrets not having met Kurt Sanderling, who had just been appointed principal conductor of the BSO, and hopes to do so on his next trip to the GDR. Letter 2 (Moscow 1949): The composer thanks the conductor for his interpretation of the Fifth Symphony.

Kurt Sanderling quote: From Tobias Niederschlag’s interview with the conductor (2010). Published in the publication commemorating the Sanderling Homage, 2011.