11.00 Uhr

cappella academica, Christiane Silber

The oboe is April's instrument of the month. Anyone who plays them not only has to practice, practice, practice, but also cut into thirds, shorten, plane, scrape and much more. We asked solo oboist Michaela Kuntz about her instrument.

When I was three years old, my father began teaching me the sopranino recorder. As a 5 or 6-year-old, I practised three hours a day before competitions. You can still see the imprints of my milk teeth on my little recorder, because I sometimes bit the wood in anger when I had to keep repeating a passage (laughs).

But this basic discipline helped me out later on. When I was about 9 years old, my father placed an oboe and a flute on the table one day. I was supposed to try both instruments and then choose one. Although the oboe meant I had to play through a reed, I decided for it because I liked its sound. My parents always encouraged me, but becoming a full-time musician was my wish alone.

My mother actually had my first oboe teacher show her how to make reeds for me. I usually did well with her reeds – if I didn’t, I simply folded them over. That irked her somewhat, of course. I didn’t really appreciate the art of reed-making until I started doing it myself (laughs). It was only then that I understood how much time and effort goes into making a reed.

Dexterity and fine motor skills, I’d say. And a tolerance for frustration, because the raw material is a natural product, which is always different. Even if you technically master the individual steps, what looks like a reed may not sound like one. You can buy cane in different production steps and shorten the process. I always do everything myself and now even grow my own cane in Albania. However, it has to mature for another two years before you can work with it.

There have actually been some developments that make reed-making easier for us. For example, new planing machines can shave the blade profile at a fairly high level.

There are also new developments in plastic reeds. These are useful when practising techniques, as you can preserve your good reeds. Many of us always have these as a stopgap in our cases. But my ability to work with plastic is restricted to a certain extent, as natural materials such as cane can be crafted with greater individuality and resonate more authentically. Every oboist makes a reed for their specific embouchure and anatomy. Every oboist’s sound is different, but all that comes down to the 10 or 11 mm of this scraped blade of cane. The reed also reacts very sensitively to many external influences, such as humidity or air pressure, and may need to be reworked.

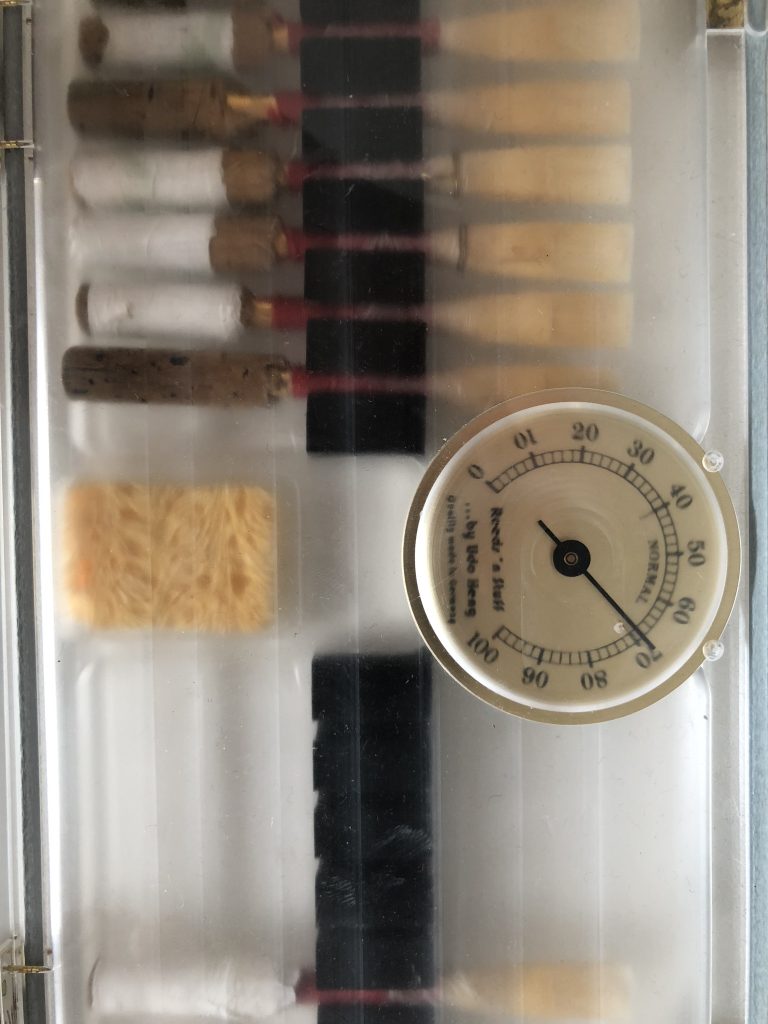

Another good idea: An ideal climate for oboe reeds. A glance at the measuring device reveals whether the humidity in the box is correct. Moisten the sponge if the air is too dry.

We oboists don’t need as much air as flutists, for example. Our problem is that we can’t always exhale of the air we breathe in. The two narrow reeds that vibrate against one another through this very small opening create greater challenges for oboists than for other woodwind players. Because the opening of the reed is very narrow, the used air, i.e. carbon dioxide, accumulates. That’s why we tend to have redder faces than flautists. It’s important from the start to learn a good breathing technique and how to expel air properly – only then can you play long phrases without any problems.

Important: Don’t forget to breathe out! The oboe reed is particularly narrow, which is why too much air can remain in the lungs – a red face does not indicate shortness of breath.

An oboe is already “played out” in about six years, which is when you should buy a new one. Oboes are subject to a gradual loss of sound and intonation. If the resistance needed for a beautiful sound is no longer in the instrument, you have to build it into the reeds. This, in turn, makes them heavier and robs you of strength and effort.

The wood is subject to constant changes with fluctuating humidity. Inside the instrument, the breath makes the wood warm and damp; outside, the atmosphere in a concert hall affects the wood – for example, air conditioning makes the air cold and dry. Wood stress, which is already very high in the oboe compared to other instruments because of its mechanics, is also affected by temperature and humidity fluctuations. New oboes are particularly susceptible to the risk of the wood cracking.

I have never heard of a bassoon or clarinet cracking. For us oboists, I’m sure it’s happened to every musician at some point or other.

Once, a new oboe I was playing cracked in the middle of a concert during a tutti at the end of a symphony. I had nine bars free and then was supposed to play a quiet high solo. All that came out were squeaks! You sit there embarrassed and go to an oboe repair specialist afterwards. Even if you have checked everything carefully beforehand – there is always a risk of cracking.

Photos: Tobias Kruse/OSTKREUZ (cover photo); private archive